District Unearths Racial Inequities in Remote Learning

A district report finds that students of color are disproportionally choosing the full-remote option.

Photo Courtesy of MUFSD Board of Education

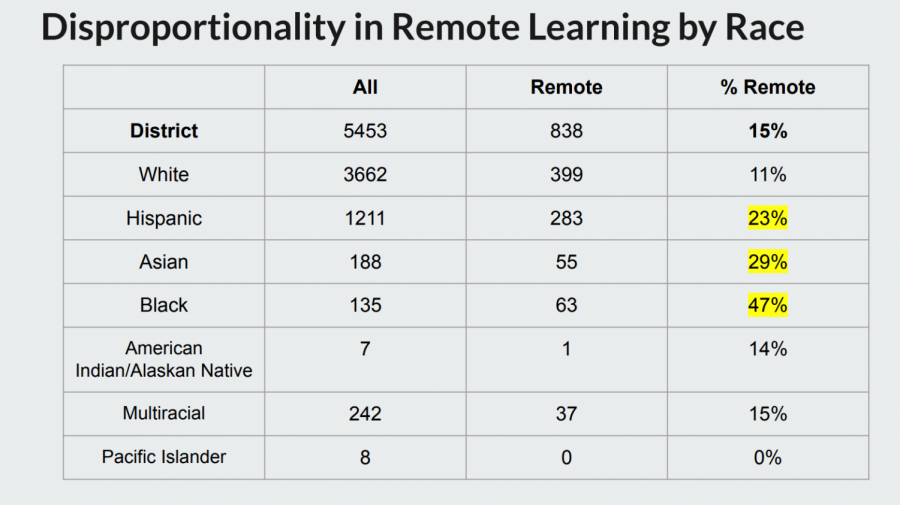

Table presented at the November 1st Board of Education meeting.

December 21, 2020

On November 2, the MUFSD Board of Education held a presentation to update parents, students, and community members on both the remote and hybrid learning models. Towards the end of the night’s presentation, a shocking statistic was revealed: While 15 percent of all students in the district were remote, only 11 percent of the population of white students were remote, contrasting with the 23 percent of Hispanic students, 29 percent of Asian students, and 47 percent of Black students learning entirely remotely.

However, this trend is not unique to Mamaroneck. The NYS Department of Health released a “COVID-19 Report Card” which includes data regarding hybrid and remote students from nearly every school in New York State. An analysis by The Education Trust of New York on this data found that “students from low-income backgrounds and students of color are much more likely than wealthier students and White students to be learning fully online.” They express concern at these statistics as, “the disproportionate reliance on remote learning for students who were underserved even before the pandemic raises significant educational equity questions.” In school districts across the state (not including the New York City, Buffalo, Rochester, Syracuse, and Yonkers’ public schools), those with more low income students and students of color are 1.6 to 2.1 times more likely to be learning remotely.

Now for the most important question, and one that many parents, students, and educators found themselves asking after the presentation on November 2nd: What does this mean?

Why are students of color more likely to choose remote learning?

MHS Principal Elizabeth Clain explains how, in her view, the disparity in the racial makeup of remote students often stems from situations at home. According to Clain, students of color and students of disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to live with elderly family members or have parents unable to transport their children to and from school on a fluctuating half-day schedule. The administration is aware of these situations and tries its best to provide the necessary support for every student, whether remote or in the building. Clain expresses how, “every family has a particular story,” and that she “feel[s] very confident that, between [herself] and [her] team, any kid who is in a position that [they] are worried about is on [their] radar.”

Doly Lugo, who teaches Spanish 2 Honors and 4 at MHS to freshman, juniors, and seniors, has seen this trend in her classes. She describes how, “about half of [her] Hispanic students are fully remote.” Lugo then goes on to explain, “Many of them live with extended family and are worried about older relatives getting sick.” However, despite the circumstances, Lugo “must say [her students] are all working well from home and completing their assignments on time.”

Lugo and several other teachers find that the largest challenge with all remote students is establishing connections, as activities such as icebreakers and games aren’t practical. Mary-Beth Jordan, who teaches English to freshmen and sophomores, remarks, “What’s lost in translation between the classroom and Zoom are things like trust, a sense of humor, and just the usual small talk about what’s going on in student lives, the little ways we find to connect.” With these little things also come bigger issues like a loss of understanding and the inability to catch up if a student falls behind. Robert Hohn, who teaches computer science and Algebra 2 Honors to freshmen and sophomores adds, “If a student doesn’t actively seek me out for assistance, then my attention automatically shifts to someone who is letting me know they need help. So, if a student is always volunteering to answer questions and/or always asking for help, I will likely be spending more contact time with them—regardless of whether they’re in-person or remote.”

What are the long term impacts on the quality of education of remote students?

When asked whether she worries about the education of her remote students, Lugo replied, “Yes, I worry. In a language class, [remote learning] makes a significant difference. I hope [remote students] feel comfortable enough to speak up if there are unforeseen circumstances that prevent them from doing their work, but I fear there are some issues that will not be known to me.”

Dr. Storey Trush, a school psychologist at MHS, adds to Lugo’s comments, saying, “Access and engagement are problems that are impacting students in schools everywhere. These issues include practical and financial constraints, such as technology and connectivity issues, as well as emotionally-based struggles, such as students not logging into their classes or participating in lessons and discussions.”

These educational disparities may have unforeseen long-term impact on remote students, possibly putting them at a disadvantage later on. Trush connects the education consequences of remote learning with the demographic information revealed by the Board of Education stating how, “it may serve as another example of structural racism, in that it limits the pathways that certain groups have to access opportunities and upward mobility.” She then goes on to urge, “As a district and community we need to think about why this is happening nationwide and what can be done to level the playing field.” Trush stresses that, “it’s never too late, and our attention to the matter puts us in the position to make meaningful changes.”

What can be done to help?

Despite the circumstances, and the continuously “herculean“ effort of teachers, according to Trush, teachers in the MHS community have been accommodating for all their fully-remote students, trying to create that connection they feel is lost across the screen. Jordan describes how she reached out to parents of her students by email at the start of the year. In doing so, she “was able to create one more channel by which to connect to students. That way, if [she] needed to reach out or get parental support, [she] had already introduced [herself].” Hohn is using similar methods and also encourages his students to give him feedback for how he could improve. He states how he “considers [himself] to be a pretty “open” person who’s always looking to better himself,” and is always “open to any suggestions that students might have!”

Trush herself also tries to make these changes in her work as a psychologist. She says how “when [she] meets with remote students, particularly students of color, [she] tries to create a safe space where they can process the multidetermined reasons for their decision to learn remotely.” She consistently “approaches this subject with a genuine sense of openness, empathy and curiosity”.”

Kelly Carrillo, also a school psychologist, has been “making sure that students have access to devices that work properly so that they can stay actively engaged.” She adds, “It has also been important to understand some of the stresses a family may be experiencing that might be impacting the student.” and that “Connecting the families with resources can be helpful.”

The district will continue to monitor the situation with all remote students to make sure that all students are provided just opportunities for learning. Additionally, the district is working with an equity team and implementing an equity plan across all schools to address systemic inequalities in education. In the meantime, students can foster the spirit of community at MHS by reaching out to their peers and teachers to bridge the gap between remote and hybrid students.