The Rise and Fall of the Plexiglass Dividers

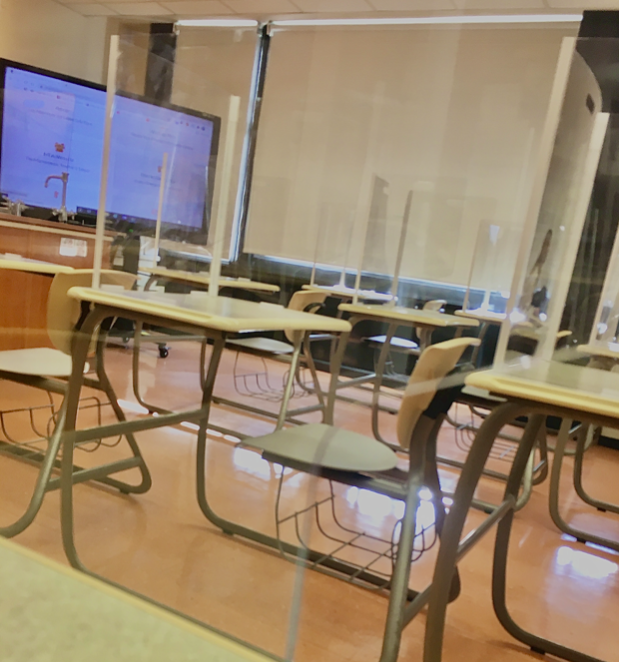

Desks in a Post science classroom encased in plexiglass shields.

June 23, 2021

One day they rose, and one day they fell. The mighty plexiglass dividers once stood sentry on the desks at MHS, guarding against the transmission of COVID-19. But just as mountains form and then tumble earthward, and just as the flightless dodo lurks no more, Mamaroneck High School’s plexiglass dividers have become extinct.

Were the dinosaurs despised by other species? Such a feeling seems to have been what caused the fate of the plexiglass barriers. In a recent poll, most members of the Mamaroneck Teachers Association voted against their use. Students, too, did not like them. As one tenth-grade student explained, “They were wobbly, so any slight movement [made] the whole thing shake. If you look up plexiglass, obviously it’s clear. But this was some temporary, low-quality plexiglass that made it so you had to look above the glass or around it to see what was written on the board. This defeated the whole purpose of the plexiglass.” Not long after being installed, the barriers started being removed. No one seems to be mourning their loss.

At a time when infection rates are dropping precipitously, and vaccines are readily available even for teenagers, it is easy to wonder why the barriers were installed in the first place. But the answer to that lies in the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) guidance for schools on how to safely reopen. As far back as last December, the CDC issued a set of guidelines called “K-12 Schools COVID-19 Mitigation Toolkit.” Among the dozens of recommended strategies the CDC included on its checklist was the following: “[…] physical barriers, such as sneeze guards and partitions, [should be] installed in areas where it is difficult for people to maintain a 6-foot distance from each other.” The implication was that the reasonable approach was to install such barriers in classrooms. Indeed, in their February guidelines for reopening schools, the CDC noted that “All mitigation strategies provide some level of protection, and layered strategies implemented concurrently provide the greatest level of protection.” This perspective encourages schools to try everything possible to minimize the risk of infection to students and staff.

After infection rates peaked in January and began to fall, though, some experts reconsidered the need for physical barriers in classrooms. In mid-February, the New York Times published the results of a survey of 175 pediatric disease experts who were asked to rank potential mitigation strategies in schools. Out of ten different strategies, masking, social distancing, and proper ventilation constituted the top three. Physical barriers were ranked as being of the least importance. Experts’ gradual de-emphasis on plexiglass as a mitigation strategy may be why, once installed at MHS, plexiglass was nonetheless quickly found to be inessential.

Still, the CDC has not completely walked away from touting the usefulness of dividers. Even now, its website states that plexiglass dividers between teachers and students remain useful in cases where those individuals cannot maintain social distancing. Mary Crean, the MHS school nurse, is in accord with the CDC’s perspective, as she recognizes that barriers may serve a purpose in certain situations. Crean says, “The plexiglass divider may serve as an extra layer of protection. If someone is sneezing or coughing, it may be helpful. However, it is most important that everyone continue to wear a mask, wash their hands, and maintain social distancing.”

But now that the plexiglass dividers are being removed, what will happen with them? What are the environmental ramifications for their disposal? Heather Rinaldi, the faculty advisor for the Eco Reps sustainability club, observed, “Obviously, one of my first thoughts when I heard about the dividers being installed was related to the amount of plastic being used, and not just here in Mamaroneck, but all over the country. Unfortunately, we live in a society where too much of our ‘garbage’ gets thrown into the trash instead of being repurposed or reused. Each day, there are little changes we can all make to lessen our carbon footprints like minimizing our consumption of single-use plastics. This might be a bigger undertaking but I am certain that, if given the opportunity, the MHS community would be able to come up with a creative alternative to throwing this plastic away.” Whatever the ramifications of disposing of the plexiglass, however, those challenges do not justify reinstalling them. Given that most teachers and students objected to their use, it appears that the dividers diminished the classroom experience. At the end of a long and challenging pandemic year, that is the last thing anyone needs.

The pandemic is not over, but it seems that the glory days of the plexiglass dividers have come to an end. Perhaps they will be succeeded by other mitigation strategies that scientists have not even invented yet. Maybe some of those strategies will be longer lasting, or maybe not. Ideally, unlike the plexiglass, newer mitigation strategies will be neither despised, nor largely unnecessary. It may also be that the school’s experience with the short-lived plexiglass will make it more skeptical of implementing measures that go beyond masking, social distancing, and proper ventilation. The only certainty we have is that we are living through strange times, when what is new is not only a novel virus, but also the particular means used to fight it.