We Shouldn’t Reduce Our Classmates to ‘Try-Hards’

Why identifying other students based on their level of academic achievement is harmful and how future MHS classes can change for the better.

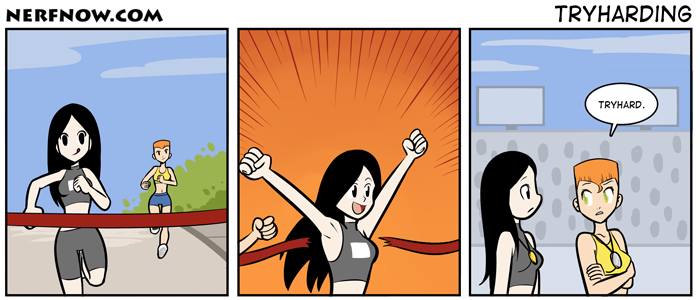

Cartoon Courtesy of Chariot Learning

Jealous participant in race reduces the winners efforts to being a “try-hard”.

February 28, 2022

According to Urban Dictionary user Psalhf, a try-hard is “somebody whose effort level and emotional investment [are] excessively high” for their situation. In other words, as put by user prl215, they are “someone who f****ing freaks out when they get below a 95 on a test.”

In the MHS Class of 2022, there has always been an interesting culture surrounding try-hards. From grade sharing circles spawning in middle school email chains, to the echo chamber of who applied to/got into/got rejected from “elite” universities, we evaluate the social merits of our peers based on numerical reflections of their intelligence or the frequency with which they comment in class. When someone is labeled a try-hard, it acts as an indicator of social incompatibility and implies that they are annoying. Yet at the same time, many students continue to “try hard” to pursue success in our grades, class difficulty, and college aspirations.

As someone who has been directly named a try-hard multiple times (mostly concentrated in freshman and sophomore year), I think it’s time that we reconsider what this culture does to those students labeled with the term, those that use it, and those who simply spectate the whole ordeal.

At a young age, the “goodie-two-shoes” behavior, which we now label as annoying, was rewarded. For some, those rewards became more than just an incentive to not bully another six-year-old on a playground, they became a marker of identity. I distinctly remember a green-yellow-red card behavior system in my second-grade class, as well as how upset I was when my consistently green card was turned to yellow by a substitute teacher. A perfect green streak was a necessity because it gave me a feeling of value, a feeling that still needs to be maintained to this day.

“A lot of perfectionists tend to do more work than they need to because they seek validation from others,” states Elle Krywosa (‘22), “but also from themselves, in the sense that they want to reassure themselves that they’re doing the best they can.” She, too, considers herself to fall into the categories of try-hard and perfectionist. In her eyes, those who want so hard to meet impossible standards, “end up doing more subconsciously out of [the] fear that someone else could be out-hustling them.”

Everyone has internal pressures that they put on themselves. Calling someone a try-hard externalizes these pressures and turns them into a social currency. What are you to do when you feel that meeting your own internal standards, a main part of your identity in the eyes of your peers, simultaneously isolates you from them?

You change the way you present yourself, but don’t change the motivations under the surface.

In speaking with eight high-achieving seniors about this issue, I found that almost all of them indicated in some way that in the past four years, they’ve changed how they speak in order to be less assertive or obvious about their academic investment around others. One anonymous senior reflected how over time, they’ve “tried to be less assertive in a negative way and more ‘go with the flow’” when interacting with peers. They spoke of how they, “also use a lot of qualifiers (ex: ‘I’m probably wrong but…’, ‘I have no idea what I’m doing but…’) when [they’re] speaking so as not to appear overly confident.” Another commented how, “subconsciously, I definitely have tried not to let on how much I care about school to others.” They’ve tried to appear as though the title of try-hard doesn’t fit them because that title can only be a bad social omen.

“I’d be lying if I said after being called a “try-hard,” I didn’t tone my class persona down a bit in response,” states Jackson Owens (‘22). He reflects how, over time, “the actions of correcting people, caring way too much about details in class, and falling into the trap of providing random people with homework answers slowly fell away from me. I have put myself out there less I guess, and I think I’ve become more conformist because of it.” This conformity, however, has not changed his attitude towards academics, only his “class persona.” He believes that, “if you’re already dedicated enough to be annoying enough to warrant being labeled a ‘try-hard’, you’re not going to be dissuaded from pursuing further academic achievement by simple name-calling.”

Again, we change ourselves, but don’t change the motivations under the surface.

From when we first entered MHS to now, the extent to which we name-call and judge those who care about academics has most certainly decreased. Especially starting in junior year, with the introduction of AP classes, academic stress has become more of a collective endeavor–a bonding opportunity, if you will. But the connotation that we have with certain high-achieving students (try-hards), knowing that they’ve cared this much and supposedly achieved at this level for so long, has not diminished.

I don’t feel relieved from the pressures of being expected to score high and understand what’s going on at all times just because everyone else feels those pressures, I just act as if those expectations have been alleviated in order to become more palatable to others. And yet, I don’t feel alleviated from the feeling of social isolation that comes from being identified as a ‘try-hard’ in years prior. To this day I attribute any negative interaction with my peers to their awareness of my predetermined social identity as someone who doesn’t have the capacity for anything beyond academic achievement. At this point, it’s difficult to deduce which parts of my academic action come from my own ambitions and which parts of that come from feeling as though I need to be that way in order to fulfill the expectations of others.

There is also, of course, the aspect of gender. Anna McDonald (‘22) recognizes how at MHS, “while driven male students are perceived to be admirable, well-rounded individuals with a variety of interests, [she] often finds that female students with the same level of academic intensity are reduced down to their strengths as a student.” Another anonymous senior commented how, “there’s a lot more room for boys to be arrogant about being smart. There’s this pressure for girls to keep it under wrapped or hidden.”

So where does all this leave us?

For our senior class, as we reach the end of our time at MHS, it is worthwhile to reflect on how what we’ve been labeled here has impacted how we think we are perceived and how we subsequently perceive ourselves. We are all multi-faceted individuals with the potential for so much more than what those around us may reduce us to, even if our peers have told us otherwise.

For all the other current and future MHS classes, especially underclassmen, don’t reduce one another to what each of you appears to be. Academic achievement is only one part of someone until you make it their everything–until you make them a try-hard. The motivations for that achievement can have many different roots beyond just wanting attention or being annoyingly smart. Ultimately, you are all students, but you are also people. People who don’t deserve to be limited to just a singular term.